St Francis of the Birdbath

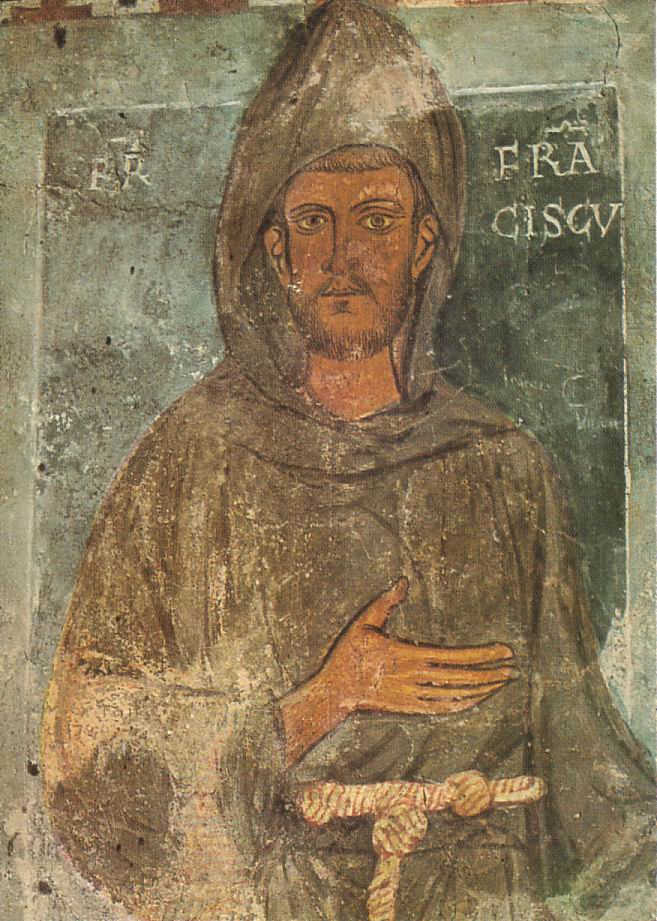

4 October is the feast day of St Francis of Assisi. You might know him as the irreverent but apt moniker, St Francis of the Birdbath, because that is where many of us encounter him. Bare-headed with the monk’s tonsure, dressed in rough robes and coarse rope belting, he stands with one palm out, feeding the birds from his hands. Francis is so deeply associated with humble poverty and natural surroundings that we tend to forget that this was a man who had dealings with the most powerful people in the world of his time. He had the ear of many rulers, secular and religious alike. He traveled to Egypt and Jerusalem, converting, it is said, the Sultan of Egypt, al-Kamil, a nephew of Saladin. He obtained papal permission to found three religious orders and created the rules and a good deal of the infrastructure for each himself. He preached to commoners and made renouncing wealth the central tenet of his view of the world, but it must be said that he had wealth to renounce.

Francis was born in Assisi in 1182 (or perhaps late 1181) to wealthy parents, an Italian father and a French mother, from whom he gained his nickname. His father called him Francesco, “the little Frenchman”. It could also be translated as “the freeman”, but as he was the baby of a wealthy merchant, this doesn’t make much sense. In any case, his given name, Giovanni, is largely forgotten.

Also forgotten is his early life, which was quite typical for the son of a rich merchant, but not at all expected from the boy who would become a saint — though that does seem to be a common theme of saintly youth. He was enamored of troubadours and spent a good deal of his father’s money on flashy clothing and loud parties. However, there is evidence that he became disillusioned with this life well before he reached adulthood. As a young adult, he had several visions that led to squandering his father’s money on less “noble”, but far more honorable, pursuits. Repairing the roof of the local church he prayed in, for one example — with money that he all but stole from his father’s shop. Before his thirtieth birthday, he had been kicked out of his home and had renounced his family and former life. Not much time later he began to gather followers, “friars”, who likewise embraced poverty and turned their lives to stewardship, preaching to the soul while tending to the body.

Francis was beloved by all when alive — still is now. He is one of the very few Christians of whom this can be said. There are many Christians who command respect; there aren’t many who inspire love. I would like to have known Francis. I think many people feel the same. Certainly, his contemporaries tell us explicitly that he was loved, that to know him was to want to be near him, to want to be like him. Francis, himself, desired above all to emulate the life of Jesus (who, it must be said, was also a deeply caring man who was beloved by all who knew him). Francis was sincere, devout, and honestly committed to giving of himself to others. And he made no distinctions. Not even between humans and other beings. He famously called the moon and sun, wind and rain and rivers, his sisters and brothers. He lived with lepers. In The Little Flowers of St Francis, a collection of folktales that sprang up in his wake, we see him talking with animals as often as with humans. He probably did, in fact, feed birds from his hand.

But what I find astonishing about Francis is his view of deity. In fact, I am amazed he wasn’t burned for his ideas which were and still are in no way accepted in the Church — though with the present Francis that might be changing. Francis believed that all is holy. All contains God. All is God. Not merely humanity, but everything. Francis saw deity in all things and all things were holy to him. There was no need for mediation. God was living in every heart, animating every creature, talking with every voice. There was no need for sacred space. All places were sacrosanct because all places were filled with Presence. God tended to all things. God caused all things to be and to be well. God was in the world.

This was and still is radical stuff. I am unsure — because he never used these terms, indeed, he hardly wrote anything but his rules — whether he thought of deity as something that is wholly bound up in this world, pantheism, or if he thought there might be enough of God to both pervade this world and transcend it, panentheism. I don’t know if he would have cared enough to argue the point. He was concerned with life in this world; that is abundantly clear. He hardly talks at all about salvation or life after death. He talks a great deal about right living now, about how we make good lives, for ourselves and for others. Moreover, he lived that right life, showing us the path, not merely pointing to it with words. He may have believed in transcendence, but he lived the life of a thoroughly rooted Earth-being who cared a great deal about all the other Earth-beings alive with him. What happened after that good Earth-being life was irrelevant.

To my mind, he is the closest any Christian has ever come to being like Christ. And yet, Francis was never even ordained as a priest. He was never part of the hierarchy of the Church*. And though his influence was great, though he was sainted within a few years of his death so venerated was he, it seems to me that the Church didn’t learn much from him in the long run. History might have been very different if Francis’ message of a sacred world had been accepted by all. But as I said, that might be changing now. There is a Pope who has taken on the name of Francis. From all that Pope has said and done so far, it seems his sincere intention to take on the message of Francis as well.

Maybe now we’re ready for that message — that everything is sacred, everything is deity. Maybe we’re ready to truly listen and learn from Francis. Maybe we’re even ready to emulate Francis… rather than merely standing his mute effigy out by the birdbath.

*This was edited for clarification from “never part of the Church” to “never part of the hierarchy of the Church”. Thanks to Luis Gutiérrez for the correction!

©Elizabeth Anker 2023

What is most remarkable about St. Francis is that his horizontal spirituality grew out of one of the most rigidly hierarchical (and patriarchal) religious institutions that human culture has ever created – the Roman Catholic church. It is not surprising however, that his non-hierarchical spirituality was intimately connected with a non-materialist approach to the good life. For St. Francis, Earthly riches come not from material possessions or privilege but the quality of our connection to the other beings in the web-of-life, including those humans who were “poor” in a material sense. Horizontal spirituality is a characteristic of much (most) indigenous spirituality with the notion of a hierarchical “God” or gods antithetical to their worldviews. I wonder how St. Francis would feel about the modern anarchist mantra, “no gods, no masters, no borders.”

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m not sure he would have accepted “no gods” because he thought everything was/is deity. Or at least imbued with deity. I don’t know about borders or masters. His Rule certainly recognized no leadership or limits but his God. Which was everything. So… fairly anarchic in the proper sense of the word.

LikeLike

It was Pierre-Joseph Proudhon who said, “If everyone is my brother, I have no brothers.” Does it not logically follow that if God is in everything then there is no God? Is the notion of supremely hierarchical spirit incompatible with God and gods and goddesses?

LikeLike

I don’t agree with that logical fallacy… if everything is your brother, then everything is your brother… you have infinite brothers… which may make “brother” rather an ill-defined concept, but it doesn’t unmake brotherhood. However, if everything is god, then, yes, there is no God. These are two different things. St Francis may or may not have believed in a supreme deity, a God. But he undoubtedly believed that deity was in everything, that everything was god.

Being a fairly intelligent human, it’s likely he made that logical leap… but if he’d dared to say that there is no God because all is god and there can be no hierarchy among equals, at best, he would not have been remembered… or maybe remembered as one of the many dismembered for the faith.

This is why he espoused panentheism, god in everything plus a bit extra beyond the universe. This philosophy also handles things like what comes before and after everything, something that is lacking in pure animism. Animists have to go the other illogical path and say that “It’s all always been and will always be” when we are pretty sure that’s not the actual physical case…

Not that we know… but… leaving room for a Ground of Being is expedient.

LikeLike

You are right, it’s a fallacy to try and prove or disprove the existence of God through logic. Humans have been trying to do this for millenniums. A more appropriate question regarding St. Francis’ horizontal spirituality is whether God is “in everything” or God “is everything.” The basic difference between hierarchical and horizontal spirituality is whether God (or the Great Spirit) is a separate being above existence or existence itself.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I don’t know for certain, but I think he would have said that deity is in everything but also some portion of beyond everything. And he would probably say that there is no actual God, just a sacred essence that permeates all things and more. I would call it life. Or maybe Life… 🙂

LikeLike

Whether God (or gods and goddesses) is “in” or “is” everything is a rather abstract theological conundrum. The real beauty of horizontal spirituality as practiced by St. Francis and many indigenous cultures, is how it unites the spiritual and earthly realms in the present. Heaven and hell are not some “place” you go after you die, but the here and now that societies and individuals create through their choices and lived values (values are expressed not in words but actions). Spirit is not out there somewhere, but intimately a part of everyday life.

LikeLike

Correction: Is the notion of a supremely hierarchical spirit incompatible with a truly horizontal spirituality?

LikeLike

Exactly my same thoughts on him. I recently had a book published by FPR Books and used his Canticle of the Sun as the epigraph for similar reasons.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I am looking forward to reading your book!

LikeLiked by 1 person