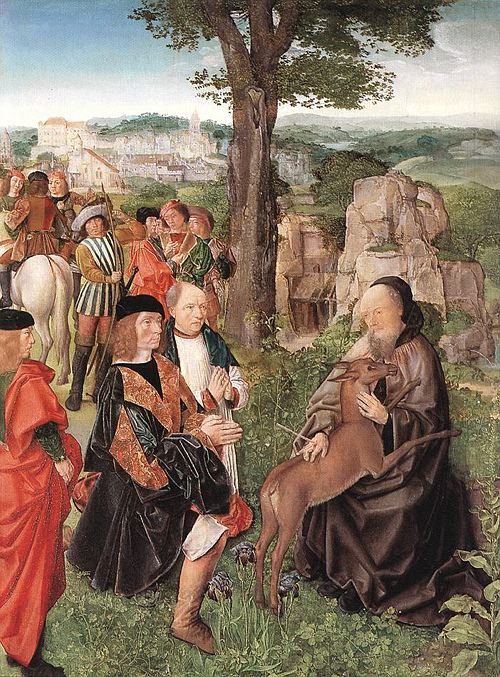

Today is the feast day of St Giles, who comes from the legendary days of Medieval Christianity. He was supposedly a 7th century prince of Athens who moved to the Rhone Valley and became a monk. He left a trail of place-names all across Europe, but he is remembered as a hermit who lived most of his days in solitude in the woods near Arles. His only companion was a red deer doe who provided him with milk. In his most well-known story — famously depicted by the Master of St Giles in the 16th century — the king’s hunters mistakenly pursued this doe. She ran to the saint for shelter just as one arrow was let loose. Giles took the arrow, protecting the deer. He was injured but not killed. He is now patron saint of the disabled.

Most versions of this story have the king bowing to the saint begging forgiveness. The king then built a monastery for Giles, Saint-Gilles-du-Gard, which Giles placed under the Benedictine Rule. This king is said to be the ruler of Septimania, King Wamba, a name that means “Big Paunch” in Gothic, a language that had all but died out by the 7th century, so clearly even the king is an anachronism in this story. But it is a good story. Later, the monastery built by a pudgy king for a holy hermit who loved a deer, became a popular stop on El Camino de Santiago, the pilgrimage to St James’ cathedral in Compostela. The abbey still stands today and is still a site of pilgrimage, particularly by women who are trying to conceive. But Giles is forever associated, not with stone walls, but the deep woods of Provence, the only place he could find god.

This urge to find deity far from human habitation, to look for god in the places that were untouched by human hands and therefore closest to god’s handiwork, was strong in the early days of the religion and remained a significant thread throughout history, finding echoes today in the writings of Thomas Merton and Thomas Berry and Karen Armstrong. As an outsider, I can’t speak to how this idea sits with those who follow the faith. It seems to contradict the currently dominant narrative of a fallen world that must be escaped through death. But it is a stubbornly persistent theme in Christianity. St Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274), following Aristotle, believed that the nature of creation was good, a reflection of deity interpenetrating all things. Reason itself, that theoretically unique faculty of man, was to be found only in studying nature and teasing out the natural laws god set in motion at creation. Law, morality, philosophy, deity — these were not to be found in books, the products of the fallible human mind, but only in nature, the perfect embodied expression of the spirit.

However, the Hebrew religion and most of the book that Christianity has claimed as its Bible, is decidedly anthropocentric and unapologetically political, indeed, often unnervingly bloody. Yahweh is a vengeful sky god who regularly takes down the many enemies of his chosen people. The Jewish Messiah is not coming to gently gather souls into heaven but to create a powerful kingdom on earth, at spear-point.

Now, remember that Jesus was Jewish.

He is not an explicitly urban figure, but there is a definite ambivalence about nature. He and his followers spend most of their time traveling up and down the Jordan River, but places distant from the proper Roman civitas (as it is expressed in the somewhat backwater Eastern Mediterranean) are associated with temptation and torment. On the other hand, the wilderness is the only place Jesus can talk with his heavenly father.

The disciples are all associated with cities, and strong political centers at that. However, by the 3rd century, when most of the books of the New Testament were written, the faithful had largely decamped to the remotest, most inaccessible parts of the desert. Now, this may be because they were being hunted down and slaughtered in horrifying fashion by Roman officials, but that doesn’t seem to be the whole story. Or maybe it is only a story.

A century or so later the Irish ascetics were building beehive hermitages overlooking the sea, finding god in living a simple life surrounded by nature. It is commonly believed that these monks preserved the Christian faith in the West as invasion after invasion convulsed the continent and Rome fled to its Eastern stronghold, Byzantium. The Irish ascetics — a tradition that has more grounding in druid training than desert monotheism — colored Christianity. It may be that the stories we read of desert fathers (and mothers, by the way, because the Irish never had much problem with strong women…) are Irish interpretations of Christian lore.

This day, or sometimes August 30th, is also the feast day of St Fiacre who is the patron saint of gardeners and herbalists. Fiachra is an ancient Irish name that may derive from fiach, “raven”. The name is found in several myths and stories dating back to the Bronze Age, including the Children of Lir, in which Fiacra is the youngest son of the sea god and the twin of Conn, whose own name means “reason” or “wisdom”.

Fiacre was the name of at least three different saints, but this feast day celebrates St Fiacre of Breuil, an Irish monk and possibly abbot, who was so skilled in healing that he garnered a cult following with hundreds flocking to seek his remedies. In the late 7th century, he left his hermitage in Kilkenny County to escape his ardent followers and find solitude in the relative wilds of France. Which… is a very common story for holy men and women from the Gaelic islands, dating back as far as Fiacre’s name. It wasn’t always France, because, of course, Gaul was the height of civility in druid times — and druids were not welcome in civil Rome. But escaping humanity to seek wisdom in the wilds is an ancient and venerable tradition among the pagans of the north, particularly those who followed the druid orders.

Druids were also well known healers and herbalists. Many core Celtic myths revolve around healing and preserving herbal knowledge. A large number of the Irish and Welsh triads, the mnemonic poetry of wisdom and law that every bard and daly memorized before being allowed to practice, describe herbal lore. (Daley, by the way, is a name derived from the Irish, dál, meaning “assembly”. Daley is a very old political family. But I digress…) Nearly all the deities and heroes in Irish and Welsh myth are healers. Even Cú Chulainn, the demigod warrior who single-handedly slayed all of Ulster’s enemies (some more than once), is skilled at healing (though that might be a native gift from his father, Lugh, who was skilled at everything).

Magical healing is a common trope in Christian hagiography, and most abbeys were libraries and experimental centers of herbal knowledge. But it must be said that this theme is at odds with a faith that so denigrated the body and this earthly life that most saints are instead known for starving themselves to death (and worse). And saintly healing is not normally a matter of training and knowledge, but a miraculous transformation brought about by a glance or a touch from holy hands. This is not at all the same as herbal healing, which is never miraculous and takes a great deal of work from both the patient and the herbalist — from growing the plants and preparing the medicines to following a health care regimen that can last for weeks, sometimes for life. And, significantly, it does not always work, though St Fiacre certainly seems to have had more successes than failures.

St Fiacre is described as an herbalist. He is the patron saint of gardeners, carrying a trowel and a gathering basket in iconography. His abbey famously produced a wide range of useful plants — food, dyes, fiber, and medicine. A thousand years later, Nicholas Culpeper, the English herbalist who literally wrote the book on the subject, still referenced Fiacre as an authority. Fiacre was not a magician or an occult healer. He was a practicing doctor. I believe he was a druid, a wisdom-keeper of the north.

St Fiacre and St Giles both sought and found wisdom not in stone halls and scrolls but under the trees, alongside the rivers, among the animals that lived beyond human control. They influenced many later Christian thinkers, from St Francis, who had a close companion also named St Giles and who shunned human company, to the late Renaissance Dominican friar, Giordano Bruno, who was burned at the stake for the heresy of finding god in everything.

Obviously, pantheism has not fared well in the Christian tradition, but I wonder if that is because it is not a Christian tradition. St Thomas Aquinas and St Francis seem to be exceptions. The desert mystics were not so much Christian as spiritualists, and while there are many ascetic traditions in the Middle East, most are not grounded in nature. They do not find god in the stark embodied magnificence of wind and sand and stone, but escape inward, seeking god in rapturous visions. Moreover, the stories we have of these early Christians come down to us filtered through a very different world view, that of the northern saints who told stories of finding god in clover and sunbeams and who practiced a rather earthy form of asceticism. There is more than a whiff of druidry in this.

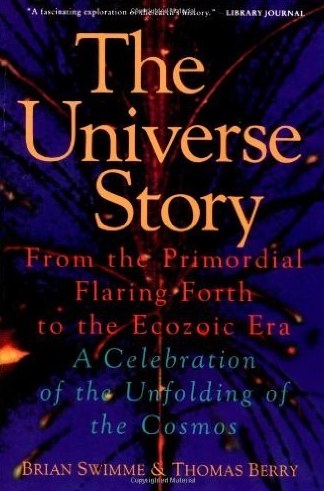

I find this absolutely delightful, particularly as this pagan-tinted Christianity seems to be steadily gaining strength. It’s been centuries since we burned people for seeing goodness in this Earth, and our current pope seems to openly embrace panentheism. The “geologian”, Thomas Berry, and the evolutionary cosmologist, Brian Swimme, rewrote Genesis, embedding deity in the universe as the ground of all being and the primal motive. The Hebrew god was never so concerned with creation, living in some distant realm, and at best, coming down to the mountain on occasion to dictate The Rules. Berry’s god is utterly entangled with life. This is nothing short of revolutionary… within the Christian tradition.

However, it is exactly how a druid might have described life. Sacred. Holy. Divine in all its parts and particulars. I’m fairly certain this seed — or perhaps acorn — of druidic thought was planted deep in Christianity by monks like Fiacre and Giles, sprouting now and then through the centuries, forcibly uprooted many times, but never extirpated. And we so need this rooted wisdom — mainly to overcome the dualist disconnection of orthodoxy, the story that man is a stranger on Earth and yet free to lay waste to this planet, indeed commanded to claim dominion over creation by a deity that cares so little for life that he would condemn nearly everything to an eternity of suffering simply for the sin of being embodied. That god is not St Fiacre’s god. That god is not Thomas Berry’s god. And I would wager that that god is not Pope Francis’s god either. I believe that god is losing ground… while the faith in a deity that enlivens and sacralizes all is rising.

Let us hope it is not too late…

Today is also the last full day of the Blueberry Moon, which goes dark tomorrow night. In my calendar, the season of Mid-autumn begins today, just ahead of the Harvest Moon. This is the season of Harvest Home, the penultimate season of the year, or the last depending on what you call Hallowe’en, the end or the beginning. Obviously, the garden harvest is a central theme. But this is also a time to consider more esoteric harvests. What have I reaped in the last thirteen moons? What have we accomplished as a community, as a culture? What shadowed the harvest? What should we never plant again? What might we try in the next annual round?

This season and this moon are a time of reckoning, a time to set aside ambitions and beginnings and prepare for the season of dearth. I think this is a relevant way to approach not just the winter, but darkening changes of all sorts. Old age, illness, the approaching death of loved ones. Preparatory grief, as it were, but also a time before the emotions become overwhelming in which to methodically put by the seeds for next season, to cultivate the strength to go on, to become ready for the end of harvest and to become reassuringly prepared for the loss to come. So that when it crashes over us, we can find those seeds and hold on to them.

This is how I am coping with biophysical collapse. I can never anticipate tomorrow’s disaster, but I can stock my toolshed and pantry reasonably well and be as generally ready as one can. I can also use this twilight time to come to terms with fear and anger — and, yes, grief — and then set those emotions aside before the darkness falls and I need all my wits about me.

Though some days, I just wallow in melancholy. And that, too, is a good way to release the season of growth, to bid farewell to the days of fresh beginnings that may never come again in my lifetime.

Here is what I find myself listening to in those grey moods… VOCES8 performing Eric Whitacre’s Home. Captivating beauty, just a knife-edge shy of lethal…

©Elizabeth Anker 2024

thanks Eliza. I was just reading Richard Rohr

« When we get away from the voices of human beings, then we really start hearing the voices of animals and trees. They start talking to us, as it were. (…) I am beginning to think that much of institutional religion is rather useless if it is not grounded in natural seeing and nature religion.

https://cac.org/daily-meditations/looking-and-listening/

This St Giles story, as you said, was probably inspiration to St Francis.

(Not saint) Gilles

LikeLiked by 1 person