It is Ash Wednesday. In the Christian calendar, this day inaugurates the fasts of Lent. This is holy time, a period of 46 days of cleansing and purging the body and soul before the celebration of Easter. The time echoes the 40 days Jesus spent in the desert before he went to his death. Originally, this purification was for penitents and grievous sinners, those who were cut off from the Eucharist and were obliged to undergo public penance before being welcomed back into the fold on Maundy Thursday. But by the 10th century this rite had fallen out of favor. Instead, the entire congregation was daubed with the penitential ashes — for a day — and then followed a strict fast of no meat and only one meal — also for a day. Between Ash Wednesday and Easter, the fast is loosened for much of the week, but each Friday is another day of abstinence in remembrance of Good Friday. The ashes are also a memento mori for each congregant. These are the palms from the previous Palm Sunday, burned and ground into the dust that each of our bodies will return to in the end.

I am not of this faith. I don’t accept that this world is cursed with sin and in need of a sacrificial cure. However, I do honor many Church traditions, among them Lent, partly because Christianity has many good lessons for humanity, and the way to learn these lessons is through participation in the ritual time of the Church. However, there are also many Christian traditions that are older than the Church, among them Lent. The name lent derives from an Old English word meaning “spring season”. Other languages name this 40-day period before Easter with words that derive from “fasting”. We can see from these names that Lent is not merely a season of preparation for the Christian Easter. In fact, its symbology and its name have little to do with Christianity. (Interestingly, the same is true of Easter itself.) Lent — or to give it its true name, Spring — is the traditional season of doing without intentionally.

Spring, the season of renewed abundance, is preceded by a time of voluntary abstinence to purge the body of winter lethargy, to draw on the strength of soul hunger, to focus our needs and cast away want. Time for sloughing off our winter flesh. We diet; we cleanse; we purge our lives of superfluous encumbrance. Consider this near universal human spring-time urge. We humans renew ourselves through restraint; we prepare for growth by accepting limits.

To some extent, this is making a virtue of necessity. Spring is the time of renewal, but there are still many weeks before that new growth produces new foodstuffs. Growth is not yet productive. What is available tends to be high in nutrients but low in caloric content — bitter greens and roots, wonderful tonic to the digestive tract but not the most filling fare. So, yes, spring fasting is not completely voluntary in traditional northern cultures. But the impulse to give up something for Lent goes beyond food. Lent is giving up luxury and excess during a time of dearth. Nobody feasts while there is famine. This is a self-imposed limit that creates communal equity and balance in society. We all give up some things, especially the more sumptuous cravings, to ensure that everybody has enough. That so many people accept these voluntary limits on consumption is evidence that our humanity still pulses through society. We are not completely heartless yet. We still have a collective soul.

I believe that we need to take this willingness to fast in spring and transmute it into a system of daily living. I believe this is how we will save ourselves from our selves. To engineer a society that will not destroy this planet, we need to become reacquainted with abundance that is not based on ever-greater levels of consuming the world’s resources. We need to viscerally feel our effects on the earth and on each other. We need to remember that we enjoy our work when work is not done solely to earn monetary income. We need a shared focus and shared traditions to bind us together, so that when we need to get down to the business of fixing all these messes, we turn to each other and cooperate. We need a routine, so that beneficent behavior is reflexive and does not depend on conscious decisions made by our monkey-brained selves — who almost without exception will choose short-term reward over all else, even personal long-term pain.

Yes, we need ritual and rhythm. We need to feel the wonder and deep connection that comes with an earth-based annual round of celebration and work. We need the surety of gathering eggs in spring and harvesting apples in autumn. We need to know what needs to be done when and why that is so. We need understanding of our planet, intimate knowledge of our place on this earth. We need forward focus. No more living irresponsibly in the moment. We need to have a framework for planning and decision-making that includes all those who have no voice now — those in the present with no agency and those in the future who are not yet born.

Our ancestors knew the value of limits. We need to live like them, live ethically once again. And that means living within some structure, within limits. Ethics are the voluntary limits we accept in order to live as a society. Ethics are how we act within the world harming none. There are physical limits to our material cultures, and we need to learn to recognize and joyfully embrace them. In practice we must incorporate these real-world limits into the ethical systems we create to limit our own actions — so that we do not take more than the planet has to give. We have lived as though there is no limit to our wants, no need for care, no desire to do life or be anything but passive receptors. We have lived like there is no future. Living in this manner is making that self-fulfilling; we are destroying the future by living limitless in the present.

It is not, as those who benefit from our system would have us believe, painful or even limiting to accept limits. Limits and ethics are boundaries that free us. We are freed of the externalities, all these harmful things that will happen when we act as though our actions have no harmful effects. There may be a few people who benefit superficially from selling billions of tiny bits of plastic, but only superficially — because even those who make money do not escape the negative effects of living in a world damaged by their own actions. To accept limits on their actions, to not do things that harm themselves and everything else, incurs far more reward and gives all of us more choice in living. Limits are liberating. You live better and with fewer constraints on health and welfare and what actually does generate real wealth if you accept limits, if you accept that you can’t do the things that make all that impossible.

This is why humans have always had ethics. Yes, we’ve spent most of our existence arguing about those limits, but until recently we’ve accepted that they exist — precisely because it is more beneficial to forego some things. Like “thou shalt not kill”. Remember that one? Maybe not very popular these days, maybe never was. But this is an ethical limit on behavior that, true, might result in some people not getting everything they want, but that on balance spreads benefit.

Now, what does this have to do with linking a life to place and to season? What do ethics have to do with ritual? How does a seasonal round of celebration put limits on our behavior? And are those limits what we need?

We treat the past as trellis, coax our vineyard through and around, and harvest is not a word for swiftness; the future harvests us, stomps us into wine, pours us back into the root system in loving libation, and we grow stronger and more potent together.

— Blue in This Is How You Lose the Time War

by Amal el-Mohtar & Max Gladstone

Well, first there’s the the obvious. Ritual holds our attention and creates a pleasurable and meaningful rhythm to life. In Lean Logic, David Fleming reminds us that repetitive celebratory ritual is how most human societies have dealt with the problem of ethical social cohesion throughout our existence, very likely before our existence, quite simply because the comforting structures of ritual make us happy. Ritual speaks to humanity in ways that pure logic does not because ritual appeals to the whole human — emotions, senses, bodily experience, belief. I can blather on propounding absolute verifiable fact at you all day long to no effect. But if I make you feel it, it becomes your truth. To convince the monkey brain to act in urge-restraining ways, we have to capture the imagination of that monkey brain and keep it busy. Ritual, celebration, living joyfully immersed in the tangible world — these things are all very pleasurably distracting! In these time-honored traditions, we find the perfect toolkit for ethical living.

Does this toolkit build the world we want? Are these the ethics we need for the future we face? Humans have flourished within the limits of celebratory seasonal, place-based living; but will this continue to be true? I might ask the opposite. In these last few centuries — the time of the limitless, untethered self — has anyone ever thrived? We have made many wondrous things, but have we derived happiness from them? Or true wealth? Or universal justice? Have we even met our basic bodily needs? If “we” includes the majority of humanity, then the answer is no. We are not thriving. If “we” includes the planet and the future, then our unethical social structures have been a catastrophic failure. It might be logical to choose the system that fosters well-being over the one that so patently does not.

But what do we need from a system of ethics in order to meet the challenges we face? The first order answer is that we need restraint. We need to accept limits, full stop. All of us. We need goals and aspirations that are not tied to consuming as much as possible of the world, some of us consuming more than is possible by stealing from what is possible for others. Living in season is a restraint. Living in place is a restraint. You will not have some options. You will no longer eat fresh tomatoes in winter. You will no longer fly to Cancun on a whim. You will no longer participate in the economy of disposable stuff. But you will no longer want to.

You will want to watch the sunset over your garden every day, giving thanks for another day of good living. You will want to knit a sweater from wool that came off the back of an alpaca you have met. You will want to fill your belly with fresh bread and potato-leek stew in deep winter. You will want to walk to the local pub and enjoy the comfort of music, friends and regional brews. You will want to nurture a tree into big beautiful leafy vibrancy. You will want to talk to chickadees. You will want to get up at 2am to watch meteorites streaking across the sky, holding hands with a person who does not need conversation from you to know the joy you are feeling. You will want to mark the time in a continual dance of ritual celebration with well-worn steps your feet remember and your soul rejoices in. This is what accepting the limits of seasonal, place-based living will bring you. I promise you this.

It is good to take on some restriction during this Lenten season. It reminds us of all the abundance that we gain from living within ethical limits.

Today is not only Ash Wednesday. There are so many holidays packed into the time between Candlemas and the Vernal Equinox, a time that used to usher in the new year, that still is the new year for billions of people. The Snow and Sap Moons are thick with observances. If you followed a traditional calendar, you would hardly have a mundane workday at this time of the year.

Which is exactly the point.

The world can not bear our mundane activities five or more days a week, every week of the year. Holidays are time out, both to appreciate our time, our lives, our world, as well as a hard stop on consuming stuff. Even on feast days there is less churning of the world into waste than there is in an average workday. Because feasts are only as much as the feasters can eat. Average workdays require us to churn out as much shit as we can regardless of whether it will be used or not. In fact, we know that most of it will go more or less directly to the landfill.

In any case, there are two other observances that are dear to me. I am sure that there are more, even within my culture. And of course, it’s autumn down south. Which adds even more ways to celebrate the time. None of which involves mundane waste.

The Navigation of Isis

In Apuleius’, The Golden Ass, we find a description of another marker of spring. The Navigium Isidis fell on what is now 5 March. This was an ancient festival even in Roman times. It formally began the Spring and opened the Mediterranean sea trading season. Apuleius describes a procession with children, priests, flowers and statuary that wound down to the docks where a specially prepared boat was blessed and “offered to the sea”. From the narrative this boat may have been a carved model; it seems to have been smaller than the priests. But it’s likely that other peoples would have offered a true ship by sending it out to sea — either to sail alone until it sank beneath the waves or to make the first successful journey of the year.

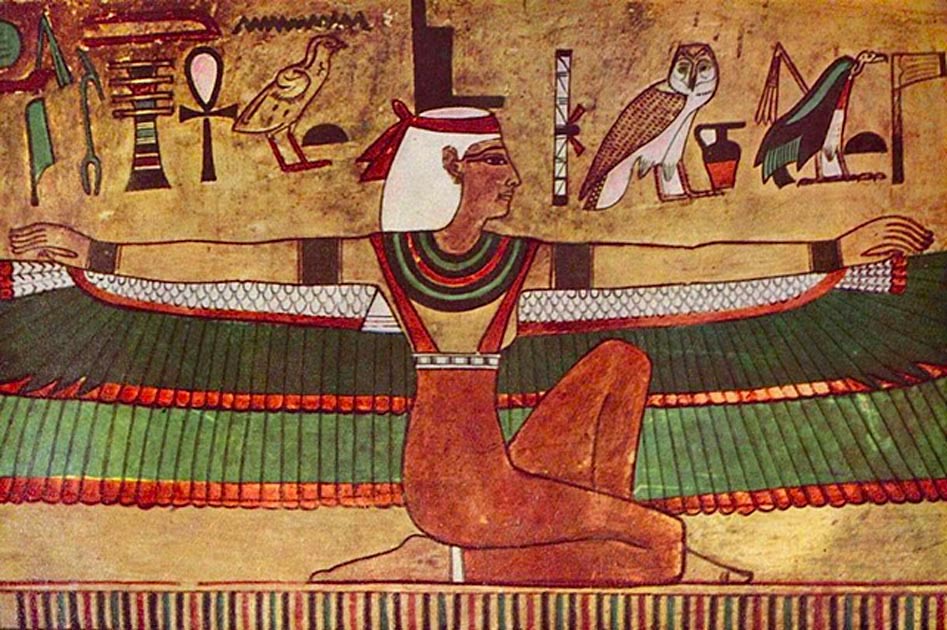

Apuleius tells us that the goddess of the sea in the 2nd century CE was Isis, even in places like Corinth where there were many native sea deities. This is odd, but it’s not likely to be an author’s liberties because there is plenty of corroborating evidence in contemporary literature and inscriptions. Though she was not associated with sailing in her native Egypt — which seems to have not had any sea gods — by the early current era, Isis seems to have subsumed the aspects of many deities all around the Mediterranean, among them sailing and sea trade. And where most sea gods tended toward indifference to humans — if not outright malevolence — Isis was a loving protector.

I suppose there is a certain sense in this. Isis is not particularly watery. She is not represented as living beneath the waves even in this late incarnation. She is a sky god, complete with feathers and stars. Seen this way, she becomes the breath of the wind that billows out the sails and the map of the skies which safely guides ships across the trackless seas. And she was a fierce mother who defended her children. She protected trade, which is always a fraught adventure. Isis smoothed the tensions between the normally belligerent Mediterranean peoples. She was the commonality that allowed commerce. She was also, from the very first, associated with bringing the changes in weather that engendered growth. She was the Spring and she created the Harvest — and the harvest is many things, successful trade dealings among them.

Perhaps the oldest celebrations of opening the seas for the year honored local deities. I can’t imagine the proud Mycenaeans choosing to worship a foreigner. But then they also weren’t much into trade. They tended more toward plunder and piracy. So I suppose their adversarial relationship with the sea mirrored their adversarial relationship with just about everything else. Still, the industrious Phoenicians seem to have honored a sea bird goddess, much like the Isis of Roman times. So there were probably others.

In any case, today our ancestors opened the Spring and welcomed Growth. So despite the frozen soil in my garden beds, I will set my ship a’sailing and put my trust in a horizon of verdant benevolence.

St Piran’s Day

St Piran was a contemporary of St David and likely another student of St Illtud, the creator of Celtic monasticism. Piran is often conflated with St Ciarán of Saigir; and because the Brythonic languages rendered the Gaelic “c” into “p”, “Piran” may simply be “Ciarán”. The facts of both lives are similar enough. Both are Irish natives born in the 5th century. Both spent time in Wales before returning to Ireland to preach to a fairly unreceptive audience. Both were summarily expelled, dumped into the Irish Sea with a rock tied to their feet, and then miraculously washed up on the shores of Cornwall where they found a kinder welcome. However, Ciarán does not become the patron saint of Cornwall; Piran does (though St Michael and St Petroc also have some claim to that). And because Cornwall’s history is centered on tin mining, Piran is also patron of tin miners.

Cornwall’s tin mines made this peninsula on the southwest of Great Britain a focus of trade that has lasted since at least the Bronze Age. Essential to making bronze, which is an alloy of copper and tin, sea merchants traveled thousands of miles to carry this ore back to the large urban centers around the Mediterranean — maybe as far east as Persia. Certainly Cornish tin has been found in Israel. This sea trade created two industries that have lasted for millennia — mining, of course, but also piracy. (Think the musical…)

The rocky and deceptively dangerous coastline of Cornwall was deeply associated with a form of piracy called wrecking — which was pretty much as it sounds, though the image of a peg-legged guy in an outsized hat is far from the reality. Men, women, rich, poor and all in between were involved in this trade, known euphemistically as “harvesting” what came from the sea. Boats were lured into rocky coves where they capsized and sent their cargoes bobbing to the shore. Women and children were sent out to retrieve the goods under cover of darkness. The goods were quickly repackaged and sold to other merchant sailors— sometimes more than once. It was a highly lucrative method of squeezing extra wealth out of trade, not unlike the modern practice of “flipping” houses (which lacks the panache of boats, of course).

Piran is not the patron of pirates — that would be St Nicholas — but his story is bound up with perilous sea travel. He first sailed to Wales as a young idealist to train as a teacher of the new religion (which it must be said also has deep ties to boats…). He returned with a new haircut and a fiery message which the Irish simply refused. (Ciarán/Piran is a contemporary of Patrick, who made all these sea voyages in reverse — and with much greater success.) The punishment meted out to the unpopular messenger was drowning. In classic Irish-mafia style, they tied a huge millstone to his feet and dumped him over a cliff into the sea. But that rock was miraculously turned into a boat of stone which carried him all the way to Cornwall, where he set about building a chapel near the coast from which to continue his evangelizing. He remained in Cornwall until his death on the 5th day of March in about the year 480CE.

Today, March 5th is the national day of Cornwall. There are parades and concerts. St Piran’s flag, a white cross on a field of black, is emblazoned on every surface. There is also a good deal of feasting and drinking over the entire first five days of March, which are called Perrantide. Tinners have a tradition claiming that many of the secrets of their trade were given to them by Piran, so on his day they leave the mines and let the saint do the work. They head off to the pub where so much alcohol is consumed that March 6th is known as “Mazey Day” and “drunk as a Perraner” was a label used throughout Cornwall in the 19th century to describe anyone who had gone well beyond the bounds of propriety. This, in a land known for its pirates…

Piran’s body is buried in Perranzabuloe, just south of Perranporth. Perranporth Beach is likely where he crawled out of the Atlantic to set up shop. Today, it is a popular parkland with flat sandy beaches and rock pools, and another type of watery adventurer can be found here. It is a favorite haunt of surfers. Those same underwater rocks that capsize boats so efficiently also push ocean waves up into rolling breakers that are fantastic surf without the dangers of strong tides and fierce weather. There are sharks… but relatively fewer pirates!

And now an announcement… The Daley is slowing down, not being a daily so much as a couple-things-a-week-ly. I think Lent is a good time for that. I almost went for a full media fast, but I probably can’t stop writing for that long. Constitutionally incapable. However, I’m also incapable of keeping up with 4-5 posts a week these days.

Part of this is to switch gears a bit. It is time to recognize that we are not facing imminent social and biophysical collapse, we are in it. Things that might have made sense when I started this project four years ago just don’t anymore. But there may be new cracks to exploit…

So… we’ll see where that leads… but it will be a slower and maybe more in depth process. I hope you’re all ok with that…

Be well!

©Elizabeth Anker 2025

What you write relating Lent to SPring makes sense for the northern hemisphere. In the southern part of the world we can still enjoy the abundance of the end of summer and whatever autumn brings. As for not posting something daily, I enjoy reading what you write and am happy to wait for whenever you feel comfortable about doing so 🙂

LikeLike