June 22nd is the feast day of St Alban, one of the first British martyrs to the Christian faith, a sort of protomartyr, in fact. It is said that Alban was beheaded by Roman authorities on this date, though the year this happened may be any time between 209 and 304.

Alban was a young man, possibly from the Roman town Verulamium, which is now named St Albans in his honor, but there is very little said of his life up until the events that led to his execution. He was probably a Christian, though he may also have simply been an earnest young man who despised the sybaritic Roman state.

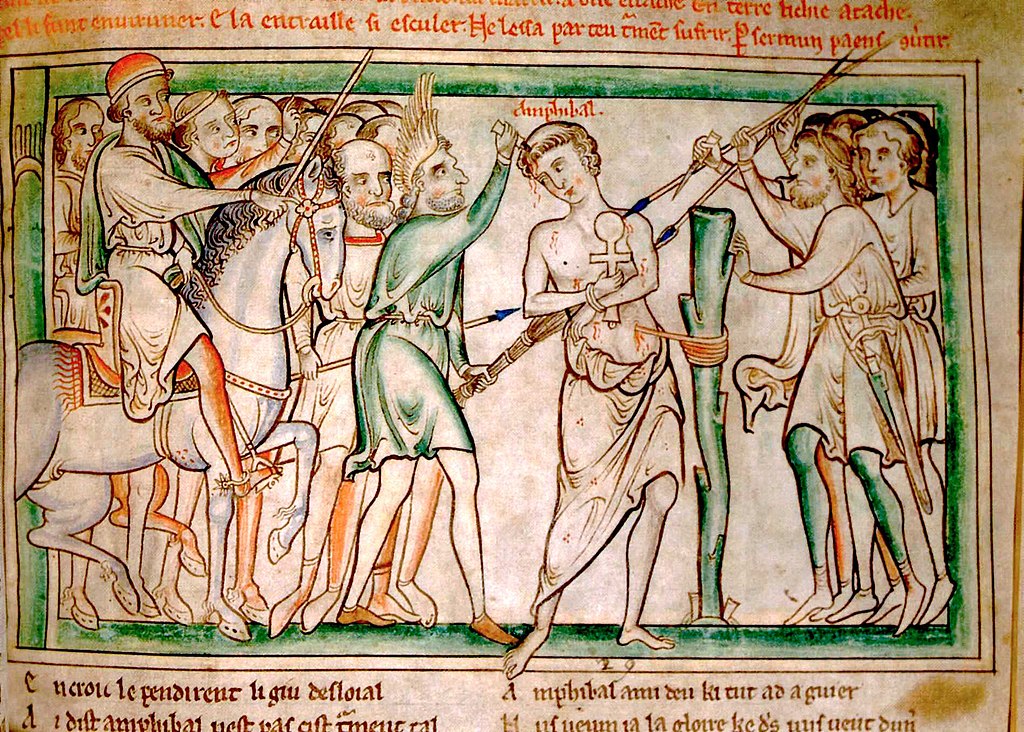

Writing some three centuries after Alban purportedly died, Gildas tells his readers that in that time Romans began to persecute Christians who convinced taxpaying citizens to turn away from the Empire and from everything the Empire revered — particularly the worldly wealth that allowed them to pay taxes. In that time, a monk fleeing this persecution landed on Alban’s doorstep one summer’s evening and Alban decided to give the man shelter. This monk’s name eventually came to be known as Amphibalus, which means “cloak” in Latin. He was unnamed in early accounts.

In the stories, the soldiers pursuing Amphibalus trace his whereabouts to Alban’s house and demand that the priest be released to the state. Alban refuses, and when it becomes clear that the soldiers will force entry into his house, Alban takes the priest’s cloak and offers himself up for capture in place of Amphibalus. Alban is taken to the authorities where he reveals that he is not the priest. This self-sacrifice seems to enrage the Roman judge all the more. Alban is given the choice between renouncing his faith and serving the rightful gods. including the Roman head of state, or suffering all the punishments awaiting the apostate, Amphibalus. Alban chooses punishment over worshipping “demons”, in Gildas’ words. The judge, believing that pain will shake the young man’s faith, gives orders that Alban should be brutally whipped; but when torture has no effect, the judge orders Alban’s execution.

Alban’s miracles begin to happen on the way to his execution. So desirous of being united with his god that he will brook no obstacles to death, he dries up a river so the execution party can cross. In causing that miracle, he converts the soldier ordered to carry out the execution. This soldier will die for his conversion.

In some tales, when they reach the summit of a hill, Alban announces that he is thirsty. His god immediately causes a spring of fresh water to gush from the rocks and Alban slakes his thirst. Then he joyfully kneels in this place and submits to beheading in this obviously holy spot. The converted soldier is killed first.

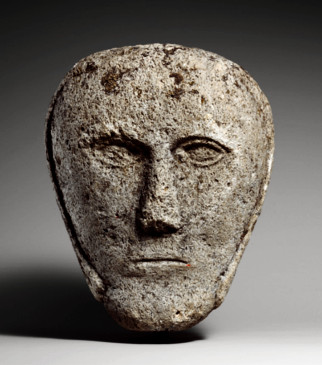

In later versions of the tale there is no appeal to higher deity. When Alban’s head is struck from his body, the eyes of his executioner fall from his head. Alban’s head is fumbled and rolls away, landing in a holly bush; and in the place where the head came to rest, clear spring-water gushes forth. This place, touched by the head of the martyr, the seat of Alban’s wisdom, becomes holy, Holywell Hill, a site of pilgrimage and supplication and healing.

Anyone familiar with the Easter story will note many similarities between Alban and Christ, including the nameless new convert who dies with the martyr. Also it’s impossible to ignore that reference to holly, still the emblem of the Winter King and of winter’s ascension over summer, as well as a symbol of Christ’s suffering and self-sacrifice.

But there is also a passing resemblance to native British stories of Bran, the protector who loses his head only to gain more power. Bran — whose name, Raven, ties him to Lugh, the über-god of the Tribe in Irish myth — is also a watery deity, son of the sea-god, Lir. King Bran watches over his family and his people until he is mortally injured in conflict with the king of Ireland. But this mishap does not end his life nor his role as protector. He instructs his people to cut his head from his body and take it home to Britain. This head continues to dispense wisdom, prophecy and protective advice for years, even conferring a sort of parallel-world bubble over his people who are grieving and injured, a place to heal — which is also a characteristic of Bran. He possesses the watery cauldron that heals wounds, even reanimating dead bodies — though the dead never recover the power of speech (so… zombies?).

Eventually the bubble is broken and his people wander back to their homelands. But Bran’s job is still not done. Through prophetic dreams, he tells his people to bury his head at the foot of a great tower. From that place the head will continue to protect Bran’s descendants for as long as the tower stands and as long as Bran’s beloved rooks gather about the tower. This is the White Tower of London, and the black crows and ravens of Bran are still in residence. In fact, the authorities are taking no chances on losing Bran’s protection these days. Many of the birds have clipped pinfeathers. They can’t fly away.

Bran and Alban share other features. Bran also created safe passage over rivers, becoming a bridge, a conduit between worlds, an intercessor and mediator, and he endures as a psychopomp to his people. Like Alban, the key parts of Bran’s story all take place in the summer, very likely at the height of summer. Most mythological battles in Irish and Brythonic myth took place between May Day and Midsummer (with most actually on May Day or Midsummer) for the very logical reason that this is also when most actual battles took place. Midsummer was battle season. It also was and remains the time of pilgrimage to holy waters and ascension up holy mountains. Bran’s healing bubble world was said to be on a wintry White Mountain in Cornwall where it, paradoxically, was always summer.

It should be noted that there is another summer feast day for a watery, beheaded martyr, the first martyr to the Christian faith, actually. The Solemnity of the Nativity of St John the Baptist is celebrated on June 24th, six months before the Nativity of Jesus.

John served as herald to Christ, gathering followers for the coming savior and washing away impurities in the holy waters of the River Jordan. His preaching eventually caught the attention of local royalty when he publicly condemned the marriage of Herod Antipas to his sister-in-law, Herodias. John was brought to Herod’s hall to entertain the wealthy with his zealot’s theatrics. However, he declined the invitation to become court jester and was duly imprisoned. He was mostly forgotten, except by one woman, the woman whose amorous advances he spurned, in some versions of the story, though other tales claim that ultimately Herodias was behind John’s death. But it’s Herod’s step-daughter, Salomé, who continued to obsess over the prisoner. Then one day, having pleased her mother’s husband in somewhat incestuous fashion, she earns one granted request from the king. She uses this boon to demand John’s head on a platter (and, yes, that is the origin of that phrase). To his credit, Herod did try to talk her out of it, but she would not settle for anything else. So John became a decapitated martyr to the Christian faith before that faith existed as such.

The martyrdom of John is observed on August 29th, six months before an average Easter Sunday, but the Church focuses on this saint’s birth, 24 June, Midsummer’s Day, the day most pre-Christian religions celebrated the solstice, the height of the Sun’s strength and the consequent end of the season of growing light. Each year, at the very apex of his power, Sol Invictus is decapitated and goes into decline from this day until Midwinter. Accordingly, throughout the world, there are myths of the Summer King whose benignant rule is ended, usually in a violent clash with the Winter Lord, on the very day that he attains full strength. This is a very old story, and Alban may or may not be a late chapter.

Alban’s name, of course, means “white”, but in a roundabout way. The roots of this Latin word are revealed in the same word for the snow-covered mountains along the north of the Italian peninsula, the Alps. This word means “high mountain” or “exalted place”, white not intrinsically, but white because it is so high and cold and puissant. To our ancient Indo-European forbears, high places were places of power, places where the sky gods ruled. Think of Olympus and the Capitoline Hill of Rome (also a heady name) where nearly all the origin stories of the Roman state are set. A tower is also a high place of deities. As is a hill of execution where the head of a martyr crowned in holly caused healing waters to flow from the stones.

From all these echoes of older stories and the lack of any verifiable information about Alban — even the place that bears his name was not recognized as the location of his martyrdom until the 7th century — it might be assumed that this is myth. The cult of St Alban began to grow in the 4th century and stories about the martyr grew with his adulation. Some stories, like the death of the converted soldier, are easily traced to older myths. Some, like the eyeballs popping out of the executioner’s head, seem like theatrical embellishment, added to the tale to enthrall and entertain Medieval wake and Whitsunday audiences. But one element hides in plain sight, and only after a bit of consideration is its possible meaning to ancient Brythonic followers revealed.

The priest is called Amphibalus, “the cloak'” a man who is concealed, one who hides from the world, especially the world of modern officialdom and foreign control. Alban becomes a martyr through taking on this priest’s cloak, by becoming the hidden man. He hides his bright white deity of mountains and towers under a shadowy mantle and willingly submits to decapitation while in this guise. Through this sacrificial act, his protection is conferred on this place. Does this not seem like a metaphor for the devious ways that people preserved their local deities? Might Alban be Bran, or a Bran-like local god, absorbed into the new religion so that his aegis will endure? Might he even be the Summer King? Will he come again like Arthur to save his people from Empire?

Whatever St Alban meant to his ancient followers, 20th century scholars are starting to wonder if Alban was an actual man. This is an important point to the Catholic and Anglican Churches. If St Alban did not live, then he did not die. He is not a martyr; he is a morality tale, a myth. He has much different status, and doubt is cast on many of the tales associated with him. For example, St Germanus of Auxerre was said to have appealed to the local saint and received intercessional aid in stamping out Britain’s Pelasgian heresy in the mid-5th century, a crucial pivot point in the political history of the Church. If Alban did not exist — or worse, if Alban was a pagan deity in new clothes — what does that mean for Germanus? Or for the Catholic Church?

Nevertheless, recent scholarship is leaning toward declaring Alban a myth and not a martyr. Seems to me that this will cause more trouble that it will solve. Alban himself is clearly sending a message to not look too closely under that cloak — because you might not like what you find.

On the other hand, pagans might be allowed to once again embrace the story and find consolation in the healing waters of Alban’s protective mountain spring. And all of us can mourn the waning strength of Sol, the Summer King, when St Alban’s Day is passed.

For the record, Alban did not save the life of Amphibalus. The Romans eventually caught up with the disrobed monk. This is the gruesome end of that story…

©Elizabeth Anker 2024

[…] The Daily: 22 June 2024 […]

LikeLike

With all that seems to keep you busy, I marvel that you find the time to post such interesting articles. Thank you!

LikeLiked by 1 person